The Value of Measurement-Based Care in Eating Disorder Treatment

This article features clips from ‘Enhancing Eating Disorder Treatment: The Value and Impact of Measurement-Based Care,’ an educational session hosted by Greenspace Health, featuring Dr. Wendy Oliver Pyatt, Chief Medical Officer at Within Health.

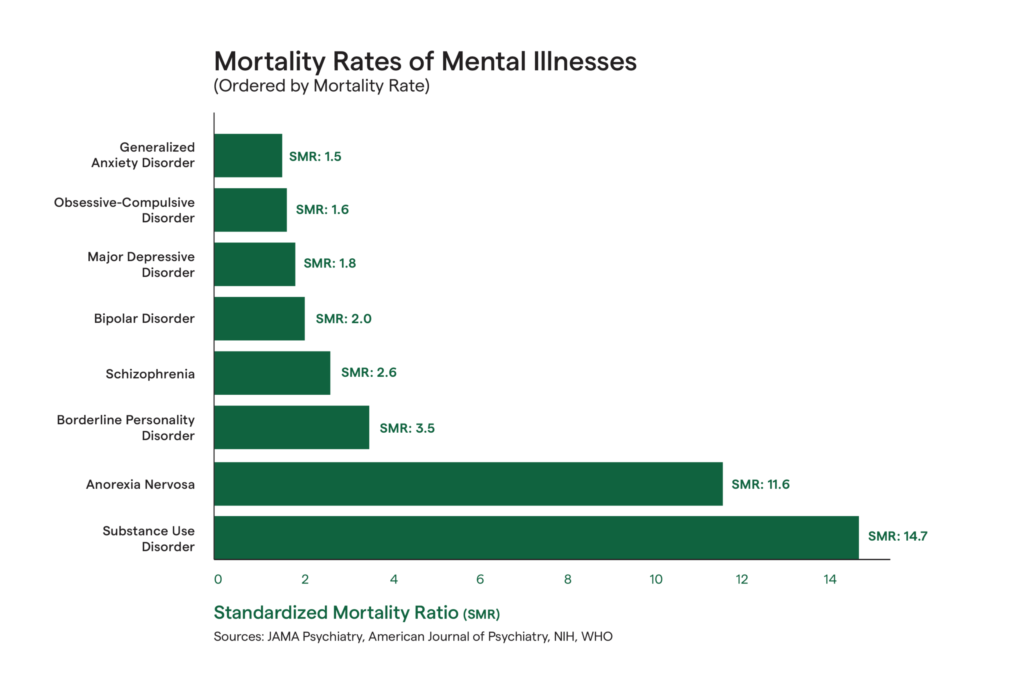

Eating disorders are the second leading cause of death among mental illnesses—surpassed only by opioid addiction—claiming a life every 52 minutes. Anorexia nervosa alone has a mortality rate estimated to be 5% to 10% over a 10-year period and up to 20% over a person’s lifetime if left untreated. This is especially alarming given that nearly 1 in 10 people will experience an eating disorder in their lifetime, yet only 20% will ever receive the treatment they need.

Given the widespread and profound impact of eating disorders, the behavioral health industry is increasingly focused on developing more effective, personalized, and evidence-based approaches to treatment. Fortunately, numerous organizations are already leading this critical work. Historically, nearly a third of individuals who access treatment do not achieve remission, however with the growing adoption of Measurement-Based Care (MBC), an emerging body of research highlights its effectiveness and positive impact within eating disorder treatment outcomes. MBC not only enhances eating disorder care quality, it also empowers providers to deliver more equitable care by better identifying and understanding the complex, co-occurring symptoms that may exist and vary across their clients or patients.

Jesse Hayman, Chief Growth Officer at Greenspace Health, discusses the major gap that exists in eating disorder treatment today and highlights the opportunity to drastically enhance the impact of care with MBC:

Understanding Eating Disorders & Treatment

Eating disorders are behavioral health conditions characterized by disturbances in a person’s relationship with food, eating habits, and their body. They encompass a range of disorders, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and more.

The prevalence of eating disorders is growing each year. Between 2000 and 2018, the percentage of the global population impacted by an eating disorder more than doubled, rising from 3.4% to 7.8%. More recent data suggests a continued upward trend, with the National Eating Disorders Association reporting a 70-80% increase in calls to its help line from 2020-2021.

Eating disorders rarely occur in isolation. In fact, an analysis of private insurance claims between 2018-2022 found that 72% of individuals with diagnosed eating disorders had one or more co-occurring mental health conditions, a statistic which increases to 97% for those who are hospitalized for an eating disorder. Studies suggest that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) impacts around 30% of those with eating disorders, more than 20% also have a substance use disorder, and anxiety and depression are highly associated with severe cases of anorexia and bulimia. Importantly, adults with a history of eating disorders face a risk of suicide that is 5-6 times higher than for those without, highlighting the critical need for early intervention, comprehensive support, and evidence-based care.

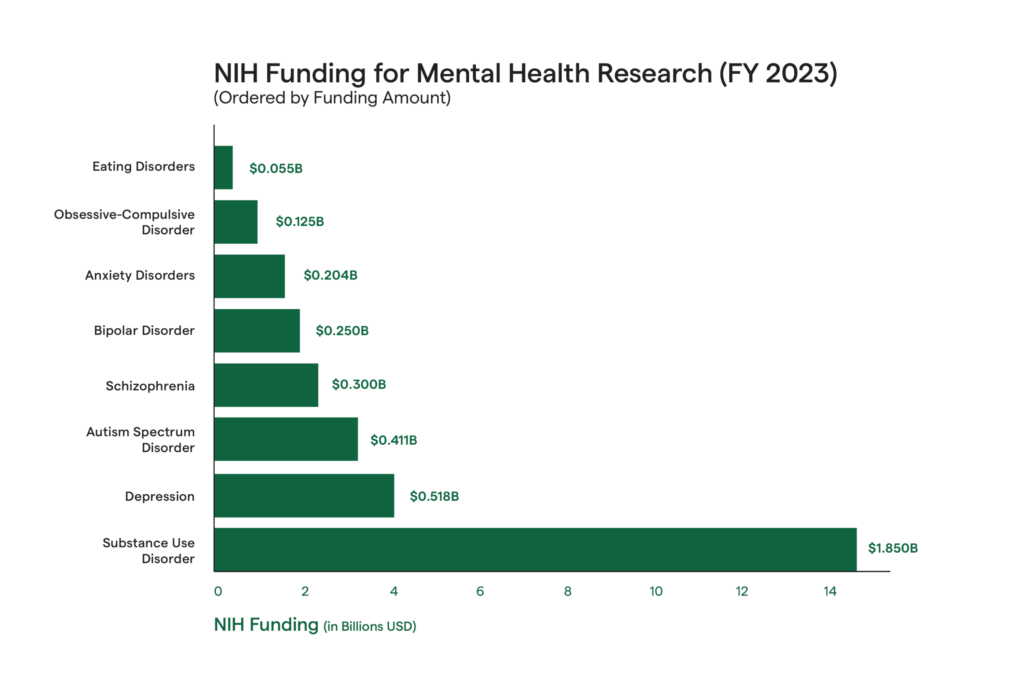

Despite their prevalence, complexity, and high mortality rates, eating disorders receive disproportionately low funding for research and treatment. In 2023, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) allocated approximately $55 million to eating disorder research, a modest figure when compared to the $1.85 billion dedicated to substance use disorders, $675 million for depression, and $267 million for anxiety disorders. This funding gap is especially concerning the elevated mortality risks tied to eating disorders. Even when accounting for prevalence, funding is still disproportionately low; take depression for example, where lifetime prevalence is 29%, about 3.5 times higher than eating disorders, yet it receives nearly 10 times more funding.

Eating disorder treatment has historically relied solely on clinical judgement, where the introduction of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) is a relatively recent advancement. With other mental health conditions, such as opioid addiction, depression, and obsessive compulsion, studies have shown considerable discrepancies between patient and clinician-reported improvement in symptoms. This discrepancy in clinician and patient goals is often attributed to the relatively high drop-out rates in eating disorder treatment, where significant differences in opinion on the patient’s needs can lead to lack of compliance in care.

Many individuals living with eating disorders do not self-identify as being unwell or needing treatment, even viewing treatment itself as a threat to their sense of self. This lack of engagement in their care can lead to treatment resistance, and ultimately impact therapeutic alliance between the clinician and patient. MBC can act as a powerful treatment tool to help proactively identify when someone is in need of critical intervention, center the patient’s voice in their care, and uncover areas where alignment is needed. It also helps to proactively flag when treatment may be off-track, allowing for timely and necessary adjustments.

The Role of MBC in Eating Disorder Treatment

MBC offers a data-driven approach to treatment by using regular patient-reported assessments to track and monitor progress and inform care discussions and decisions. When used in eating disorder treatment, MBC can help address the current challenges covered above, including low remission rates, relapse, treatment resistance,early intervention, and gaps in funding.

Its impact is so significant that the NHS recommends MBC as a core component of effective eating disorder treatment. While still in its infancy, the research on this topic shows promising results; patients receiving MBC as part of their eating disorder treatment are shown to be more likely to experience clinically significant change compared to those without it (52.95% vs 28.6%). There are a few key mechanisms of MBC that help drive outcome improvement and support recovery:

1. Individualized Care

MBC empowers providers to deliver more individualized care, as tailored measures can capture co-occurring conditions, symptom variations, and behaviors, informing treatment adjustments or any additional interventions that may be necessary or helpful. Eating disorders rarely exist on their own, and MBC enables providers to capture the complete range of experiences that individuals may face. This level of tailored intervention is critical when we consider the high-mortality rate, frequency of relapse, and overall treatment resistance impacting patients today.

In the clip below, Dr. Oliver-Pyatt offers an example of how measures can help uncover valuable insights about a clients’ symptoms and experiences, leading the path for collaborative discussions that can guide the course of treatment.

2. Equitable Services

MBC ensures that the patient’s voice is at the heart of their treatment and provides them with the language necessary to communicate their needs, experiences and goals with their provider(s), regardless of their background, community stigma or experience within care settings. Embedding equity into every service is integral to ensuring that anyone accessing eating disorder treatment receives the support they deserve, regardless of their age, gender, ethnicity, body shape and size, or socioeconomic status. In this clip, Jesse emphasizes the value of MBC in providing equitable care for individuals from all backgrounds.

3. Improved Engagement

Given that eating disorder treatment experiences higher-dropout rates than many other treatment areas, improving client engagement in treatment is necessary to increase retention and remission rates. MBC helps patients be more engaged as active participants and key contributors to their treatment. Not only does the process of completing measures and collaborating on treatment plans increase agency for patients over their own treatment, it also helps build trust and enhances the therapeutic alliance with their provider–which is the greatest predictor of positive outcomes in treatment.

4. Early intervention and relapse prevention

MBC acts as an early-signal alarm to identify when someone is in critical need of treatment, when a patient may not be responding to treatment, or when their condition is deteriorating and an alternative treatment path should be considered. This is particularly important in eating disorder treatment, as it’s estimated that 20% to 50% of patients will relapse. With anorexia specifically, up to 52% of patients will relapse at least once, typically within a year after receiving treatment. Regular measures that monitor for changes in behavioral, social, or psychological condition, are critical to identifying that a patient may be at risk of relapse. This can be done both while an individual is in care and post-discharge.

5. Data-driven Insights & Quality Improvement

Not only does MBC deliver actionable insights to clinicians to guide treatment, at an organization-level the outcome data helps clinical leaders understand the effectiveness of their different programs and services. This data is critical to informing quality improvement, treatment innovation, and funding/grant applications to improve the accessibility and quality of their eating disorder services.

6. Research & Funding Advocacy

MBC empowers individual researchers, service organizations, and health systems with the concrete data needed to advocate for increased funding. With measurable outcomes at their fingertips, they can build strong cases for expanded research investments and greater funding for direct services— a critical step toward addressing one of the most underfunded mental illnesses.

7. Effective Transition Out of Care

The effects of an eating disorder often continue after treatment is over and many clients continue to face challenges as they re-enter everyday life. Incorporating a structured, gradual transition out of care, supported by real-world exposure and guided by MBC, can ease this shift. PROMs play a key role in identifying when a client may be ready to begin transitioning and tracking their continued progress throughout the process.

Watch the clip below to see how MBC supports a thoughtful, data-informed transition out of care at Within:

Practicing MBC in Eating Disorder Treatment

At Greenspace, we often lean on the Yale Measurement-Based Care’s Collaborative ‘Collect, Share, Act’ framework for MBC. Leverage this outline as guidance for how it can be effectively incorporated throughout the care process:

Collect

As a provider, the way you engage in outcome measurement helps lay the foundation for effective MBC. There’s a few critical steps to take to ensure that patients engage with the measures and that providers can capture the complete picture of a patient’s condition.

- Explain the rationale: To ensure patients see the value of MBC, it’s important to clearly explain how the measures will be used throughout treatment. At its core, MBC is a collaborative process between clinician and patient, so they need to understand that the measures they complete will be actively and regularly discussed in session and how they will be used to improve their care. Start by describing the process, including which measures will be used and why each one was selected, how often they will be asked to complete them, and who can access their information (if anyone other than the provider). Explain how the measures will be used to collaboratively align on treatment goals, reflect on their progress, and help to adjust treatment plans as needed. Jesse explains that providing clients with a meaningful rationale as to why their completing measures and how it will be used to inform care is the most effective way to ensure consistent, active participation.

- Selecting the measures: Many programs will have a set of required measures, but it’s recommended that additional measures are leveraged based on the unique goals and needs of the patient. This can include measures for depression, anxiety, functioning, or anything else that may be a challenge in the patient’s day to day (more details on recommended measures below).

- Be consistent: Assigning measures at regular intervals throughout care is key to ensuring you can monitor symptom changes, identify challenges, and adjust treatment plans as needed.We recommend bi-weekly as a default frequency, but most evidence-based assessments will have a recommended frequency.

Share

Sharing and discussing results with patients is where the real impact of MBC lies. Whether patients have access to their own results or clinicians are sharing them at the beginning of session, when patients can see the changes in their symptoms week over week they can better understand the value of MBC and better understand the progress they are making.

The measures are designed to act as a springboard for collaborative conversations in care. You can assess whether the results align with the patient’s subjective experience, explore discrepancies in the data, and get curious about how the client understood each item, in order to build a shared language. The collaborative discussions that MBC promotes is how you can ensure that your goals are aligned and alliance is high. It’s a way to check in, ensure you’re on track, and that you’re both aligned on the direction of treatment.

Collaboration is truly the foundation of effective MBC; Jesse underscores its impact in keeping clients engaged in the following clip.

Act

‘Act’ is the time to put the data and information gathered during the ‘Share’ phase into use. This is what sets MBC apart from traditional measurement, where data collection is more of a reporting exercise without inherent clinical value. With MBC, the data is used regularly to fine tune treatment in order to optimize symptom improvement and recovery.

To get started with ‘Act’, reflect on the scores gathered to evaluate how treatment is progressing. Are you seeing improvement? Are there areas that have remained stagnant for your patient? Discuss what this might mean for your patient and brainstorm potential adjustments accordingly––on your own, with the patient, and in supervision discussions. It’s important that patients are aligned on the direction of treatment, so leverage their input in addition to your clinical judgment to identify the best possible course of action.

An important consideration in this stage is the involvement of parents, guardians, or family members in a patient’s treatment. MBC can play a key role in both determining the appropriate level of involvement, as well as in facilitating it, where the insights gathered can provide clarity behind the client’s progress, experience, and outcomes. In this clip, Jesse shares how MBC can help engage families of youth and patients in eating disorder treatment, and how this can lead to better outcomes.

Choosing Measures for Eating Disorder Treatment

There are a range of measures available to clinicians delivering eating disorder treatment—from assessments that monitor the condition itself, to measures of functioning, motivation to change, and other co-existing behavioral health conditions. Within Health offers some guidelines for measure selection from three main categories that can be useful to be leveraged within eating disorder treatment:

1. Measuring the Symptoms of Eating Disorders

This first category includes any measure that asks explicit questions about disordered eating behaviors, including restriction, body and weight concerns, and frequency of behaviors, amongst others. Recommended measures include: Eating Disorder Examination-Questionaire (EDE-Q), Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI), Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26), Eating Disorder Inventory 3 (EDI-3).

2. Measuring Functioning/Quality of Life

This category is designed to measure the impact of the eating disorder on day to day functioning and quality of life. Recommended measures include: Eating Disorders Quality of Life (EDQOL), Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA), Eating Disorder Quality of Life Scale (EDQLS).

3. Measuring Co-occurring Symptoms

It’s important to also monitor co-occurring symptoms and conditions throughout eating disorder treatment. Mood disorders, depression, and anxiety are the most important to identify and measure, but other conditions may warrant additional and more precise assessment. Recommended measures include: Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

In this clip, Dr. Wendy Oliver Pyatt shares some of the core measures used in eating disorder treatment at Within Health.

Greenspace also recommends using a therapeutic alliance measure, like the Brief-Revised Working Alliance Inventory (BR-WAI), to ensure that there is alignment between the clinician and client on the goals and direction of treatment.

For more information on implementing MBC in eating disorder treatment, check out this partner spotlight on Within Health, where we dive into their experience with MBC and how it has transformed the way their client’s experience recovery.

Conclusion

We know that eating disorders can be deadly if not treated early and effectively. With the lack of funding towards this area, MBC offers an impactful way for providers and organizations to drastically enhance care, ensure people get better, provide the support they need throughout and after care, and advocate for increased funding for research and direct services. With consistent measurement and a collaborative treatment process, MBC helps empower both patients and providers throughout the care process. With MBC at the heart of care, providers can better identify people who are struggling, are at high-risk or regressing, adjust treatment approaches early on, and leverage the data to gain the funding necessary to drive research and innovation.

Outcome data from existing MBC implementations in these settings demonstrates that we can meaningfully enhance the precision of treatment, improve client engagement, and drive better outcomes and remission rates for individuals in need of support.

To learn more about the role of MBC in eating disorder treatment and to learn practical strategies for implementation success in these settings, register for the upcoming webinar we’re hosting in collaboration with Project HEAL–a nonprofit organization in the U.S. focused on equitable treatment access for eating disorders–and Within Health.

If you’re interested in implementing MBC at your organization, you can schedule a call with one of our implementation experts or reach out to us anytime at info@greenspacehealth.com.

References & Further Reading

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

Austin, A., De Silva, U., Ilesanmi, C., Likitabhorn, T., Miller, I., Sousa Fialho, M. L., Austin, S. B., Caldwell, B., Chew, C. S. E., Chua, S. N., Dooley-Hash, S., Downs, J., El Khazen Hadati, C., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Lampert, J., Latzer, Y., Machado, P. P. P., Maguire, S., Malik, M., Meira Moser, C., … Richmond, T. K. (2023). International consensus on patient-centred outcomes in eating disorders. The Lancet Psychiatry, 10(12), 966-973. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00265-1

Bailey, A. P., Parker, A. G., Colautti, L. A., et al. (2014). Mapping the evidence for the prevention and treatment of eating disorders in young people. Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-2-5

Eating Disorder Hope. (n.d.). Anorexia nervosa – Highest mortality rate of any mental disorder: Why? Retrieved from https://www.eatingdisorderhope.com/information/anorexia/anorexia-death-rate

FAIR Health. (2023, November 15). Spotlight on eating disorders: An analysis of private healthcare claims. Retrieved from https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Spotlight%20on%20Eating%20Disorders%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

Fairburn, C. G., & Harrison, P. J. (2003). Eating disorders. The Lancet, 361(9355), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12378-1

Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

Hart, L. M., Granillo, M. T., Jorm, A. F., & Paxton, S. J. (2011). Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: A systematic review of eating disorder-specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(5), 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.004

Katella, K. (2021, June 15). Eating disorders on the rise. Yale Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/eating-disorders-pandemic

Khalsa, S. S., Portnoff, L. C., McCurdy-McKinnon, D., & Feusner, J. D. (2017). What happens after treatment? A systematic review of relapse, remission, and recovery in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-017-0145-3

Mellowspring, A. (2023). Eating disorders in the primary care setting. Primary Care, 50(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2022.10.012

New Horizons Centers. (2024, November 28). Eating disorder statistics: A comprehensive look at the numbers. Retrieved from https://www.newhorizonscenters.com/blog/eating-disorder-statistics-14c3f

NHS England, NICE, & National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2019). Adult eating disorders: Community, inpatient and intensive day patient care – Guidance for commissioners and providers (Version 1, Publication approval number: 000957). Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/aed-guidance.pdf

Rieger, E., Touyz, S. W., Swain, T., & Beumont, P. J. V. (2001). Cross-cultural research on anorexia nervosa: Assumptions regarding the role of body weight. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(2), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(200103)29:2<205::AID-EAT1010>3.0.CO;2-1

Shepherd, C. (2023). Optimizing eating disorder treatment: The case for measurement-based care. Within Health. Retrieved from https://withinhealth.com/learn/within-summit-series/optimizing-eating-disorder-treatment-the-case-for-measurement-based-care

Simon, W., Lambert, M., Busath, G., Vazquez, A., Berkeljon, A., Hyer, K., Granley, M., & Berrett, M. (2013). Effects of providing patient progress feedback and clinical support tools to psychotherapists in an inpatient eating disorders treatment program: A randomized controlled study. Psychotherapy Research, 23, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.787497

Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders (STRIPED). (2020, June). Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States of America: Report for the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders and the Academy for Eating Disorders. Retrieved from https://hsph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/STRIPED-Economic-Cost-of-ED-Report-Infographic.pdf

Subramaniam, M., Soh, P., Ong, C., Esmond Seow, L. S., Picco, L., Vaingankar, J. A., & Chong, S. A. (2014). Patient-reported outcomes in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 16(2), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/msubramaniam

Trujols, J., Portella, M. J., Iraurgi, I., Campins, M. J., Siñol, N., & de Los Cobos, J. P. (2013). Patient-reported outcome measures: Are they patient-generated, patient-centred or patient-valued? Journal of Mental Health, 22(6), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.734653

Udo, T., Bitley, S., & Grilo, C. M. (2019). Suicide attempts in US adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders. BMC Medicine, 17, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1352-3

Westwood, L. M., & Kendal, S. E. (2012). Adolescent client views towards the treatment of anorexia nervosa: A review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(6), 500–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01819.x

Zimmerman, M., McGlinchey, J. B., Posternak, M. A., Friedman, M., Attiullah, N., & Boerescu, D. (2006). How should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient’s perspective. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(1), 148–150. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.148